The Complete History of 3D Printing: From 1980 to 2022

At 3DSourced we’ve covered everything 3D printing and 3D since 2017. Our team has interviewed the most innovative 3D printing experts, tested and reviewed more than 20 of the most popular 3D printers and 3D scanners to give our honest recommendations, and written more than 500 3D printing guides over the last 5 years.

Some desktop 3D printers are inexpensive nowadays — and they can fit on your desktop or in a microwave-sized corner in your kitchen. However, this wasn’t always the case. For most of the history of 3D printing, these machines were the size of small tents, cost hundreds of thousands of dollars, and were suited only for niche projects.

You may be surprised to know that despite its appearance as a new, innovative technology, 3D printing has been around since the mid-1980s. What used to be just industrial 3D printers the size of small cranes transformed into potentially the solution to organ shortages, the housing crisis, and the democratization of manufacturing, in just 30 years.

The history of 3D printing is a long story, and we felt it was important to include everything relevant to the last 30 years of progress. We split the history of 3D printing into four main parts:

- History of 3D Printing Part 1: 1980 – 1995, Inception & early innovations in 3D printing

- History of 3D Printing Part 2: 1996 – 2009, the journey to democratization

- History of 3D Printing Part 3: 2009 – 2014: FDM & SLA patents expire, worldwide democratization of 3D printing

- History of 3D Printing Part 4: 2015 – Present – Metal 3D printing, cusp of major developments in 3D bioprinting and construction

- We also keep an up-to-date ranking of the 15 most valuable 3D printer companies.

History of 3D Printing Part 1: 1980 – 1995, Inception & early innovations in 3D printing

Who invented 3D Printing?

In May 1981, Dr Hideo Kodama at the Nagoya Municipal Industrial Research Institute published details concerning a ‘rapid prototyping‘ technique. This research was the first piece of literature to describe the layer-by-layer approach so intrinsic to 3D printing. His research involved printing photopolymers using a method which preceded stereolithography, and also spoke about cross-sectional slices of layers which lay on top of each other to form the 3D object.

However, Dr Kodama didn’t fulfil the patent application before his deadline and was never granted the patent.

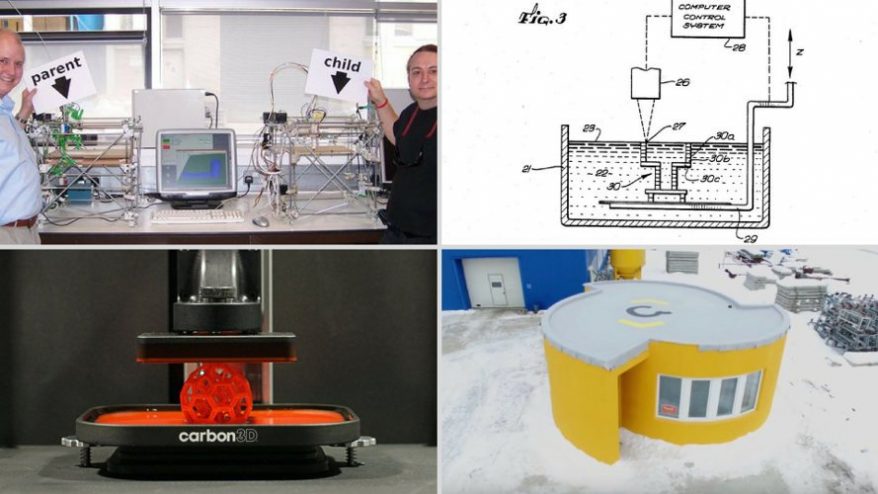

Before this however, there were rumblings and references made to a stereolithography-like process in earlier research paper dating back to the 60s and 70s, and in a 1974 New Scientist column, David Jones, writing under the name Daedalus, actually published a satirical piece that jokingly described the SLA process.

“He basically invented stereolithography with a laser, and invented it as a joke. A joke invention, but this one turned out to work!”

— Dr Adrian Bowyer, Founder of the RepRap movement, which will become important further on in 3D printing’s history.

Instead, we had to wait several more years for the birth of 3D printing. But who invented 3D printing?

1984 – 87: Early History of 3D printing & invention of Stereolithography

Three years later in 1984, three French engineers named Alain Le Méhauté, Olivier de Witte, and Jean Claude André filed a patent for the Stereolithography process. They were to pioneer a new manufacturing process that was to revolutionize manufacturing!

But it wasn’t to be. The three men abandoned the patent soon after they filed it, citing ‘lack of business perspective.’ In hindsight, I’m sure they’re gutted.

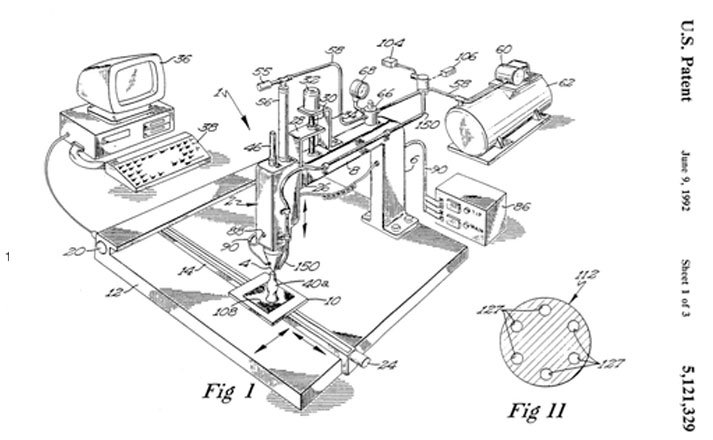

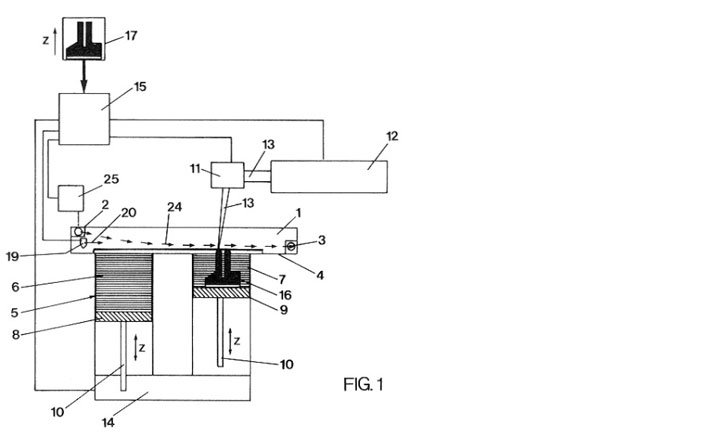

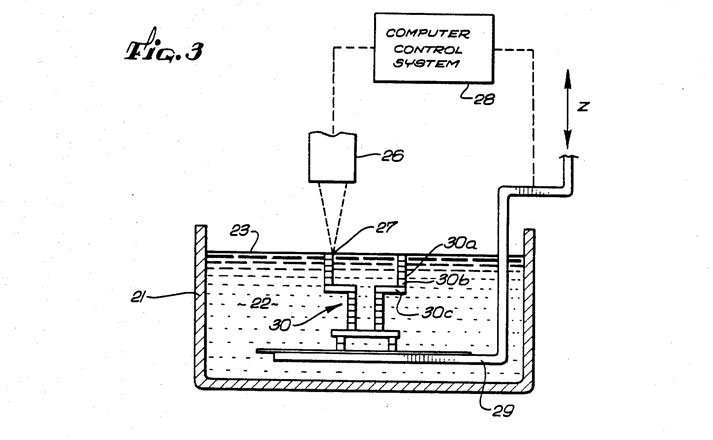

Just three weeks after the French engineers, Charles ‘Chuck’ Hull filed his patent for Stereolithography, with new features such as the STL file format and digital slicing. His process used ultraviolet light to cure photopolymers. Since filing and obtaining the patents by 1986, Chuck Hull formed 3D Systems and released the first ever 3D printer, the SLA-1, in 1987. 3D printing was born.

It is therefore arguable that either Chuck Hull or Dr Kodama invented 3D printing, though Chuck Hull is credited far more and rightfully so. Ideas are easy, executing them is the hard part.

1988 – 92: Stratasys, EOS, and FDM and SLS to rival SLA

Stereolithography had competition in the 3D printing space however, with rival processes in development. In 1988, Carl Deckard at the University of Texas filed a patent for Selective Laser Sintering (SLS) technology. Instead of using a UV light, SLS used a laser to trace and solidify layers of powder polymers. This innovative new technology was then leased to DTM Inc to use.

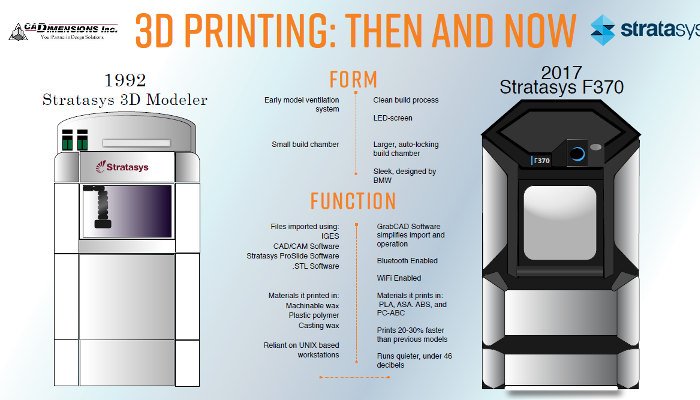

Then it became a three-horse race. Scott Crump co-founded Stratasys in 1989 and filed the patent for Fused Deposition Modeling, probably the most well-known 3D printing technology today. 3D Systems and Chuck Hull may have had a head start, but competitors were hot on his heels.

This competition was further exacerbated by the founding of EOS in 1989 in Germany by Dr Hans Langer. The German juggernaut would go on to dominate the SLS 3D printer market, as well as pioneer Direct Metal Laser Sintering in the mid-90s.

After the release of the SLA-1 a few years prior, Stratasys released their first FDM 3D printer in 1991. This was the first real competition for 3D Systems, as each had the patent rights to two very different 3D printing technologies. FDM parts were stronger and more chemically resistant, but SLA parts could be created quicker, and more accurately. Who would come out on top?

- For an up-to-date comparison of the two technologies as they are today, check out our comparison of FDM vs SLA.

The next year in 1992, DTM Inc brought out their first SLS 3D printer. It is however worth remembering that these machines were behemoths, not the compact and inexpensive desktop machines of today. They competed for industrial prototyping contracts, not to be your Christmas present. Nevertheless, the game was afoot. The three 3D printing technologies, which are still the three main plastic 3D printing technologies, were alive and kicking.

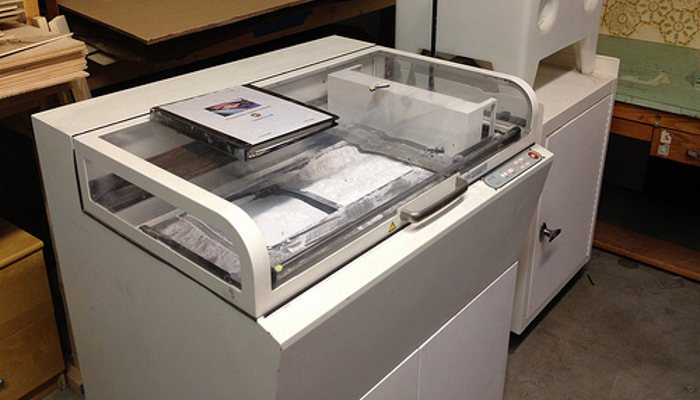

1993 – 95: ZCorp, Color Jet 3D printing, and maturation

Though less known in the modern day, ZCorp were another major 3D printing company back in the early 90s. In 1993, MIT developed a 3D printing technique based on inkjet printers – the ones we use to print in our offices on paper. Adapting this 2D technology for 3D, ZCorp released their first 3D printer, the Z Corp Z402. The technology was originally called Zprinting, though the range are now called Color Jet printers, but the technology is known as Binder Jetting. The first model used starch and plaster-based powder materials and a water-based binder to print objects.

In the same year, another novel 3D printing solution was brought closer to the market. In 1993, Royden Sanders founded Solidscape (originally called Sanders Prototype Inc.), which created wax 3D printers. These didn’t create the conventional prototypes that other technologies sought to, but instead made wax molds. These molds were then used in investment casting to create objects out of other, more solid, materials. Solidscape released the Model Maker in 1994, their first wax 3D printer, establishing itself as a favorite among jewelers creating 3D printed jewelry.

In less than ten years, 3D printing had gone from being a fanciful idea on a piece of paper to an effective niche option in small-scale manufacturing. The machines might have been big and slow, but that was the norm in 1995. Even desktop computers were expensive then. Much more was to occur however, as we will find out.

The beginning of house 3D printing

Dr Behrokh Khoshnevis, an academic based in California, first envisioned 3D printing larger layers on huge, industrial-scale printers in the mid-1990s. His focus was on creating enormous parts for airplane propellors or sand molds.

However, in the face of a number of natural disasters, he realized the potential of the technology to create shelters in record time, and for far lower costs.

“In 1994 I started thinking about large-scale fabrication with 3D printing. I wasn’t happy with the speed of fabrication of the early 3D printers, and still they haven’t changed much as far as speed is concerned. I knew there was no other way to increase the speed of 3D printing than increase the layer height, but if you increase layer height then surface quality will suffer.

“So then I came up with the idea that I call Contour Crafting, in 1994. My first patent on it was issued in 1996, a couple years after.”

- You can read our full interview with Dr Khoshnevis here.

This was just the start of what is now one of 3D printing’s most promising applications.

History of 3D Printing Part 2: 1996 – 2009, the journey to democratization

The first ten years of the history of 3D printing led to the birth of future giants such as 3D Systems, Stratasys, and EOS. Still, in the mid-1990s, they were relative minnows compared to the billion-dollar valuations they now possess.

1996 – 98: Arcam, Objet, and the first 3D printing medical breakthrough

The late 1990s was another important time for newly established 3D printing companies. 1997 saw the creation of Arcam, who specialize in metal 3D printer machines and who are the only manufacturer of Electron Beam Melting (EBM) 3D printers. Additionally, the following year saw Objet Geometries established in 1998 in Israel, who would introduce their PolyJet 3D printing technology to the world.

Stepping away from the purely commercial side of 3D printing, 1999 saw the first extraordinary achievement by 3D printing in the medical industry. Scientists at the Wake Forest Institute for Regenerative Medicine managed to 3D bioprint synthetic scaffolds of a human bladder. They then coated these scaffolds with cells from the patient’s tissue before this newly generated tissue was implanted into the patient. Since this tissue was made from the patient’s own cells, there was a low-to-zero risk of the body rejecting it, marking an important win for 3D printing in medical.

- For more information on 3D printed organs, check out our feature story on 3D bioprinting

- We also have a feature story on 3D printing in medicine

1999 – 2002: 3D printing goes multi-colored, 3D Systems take over SLS

The turn of the millennium brought another set of milestones for 3D printing. ZCorp revealed the first multi color 3D printer, whilst Objet Geometries released their first inkjet 3D printer, both in 2000. Though Stratasys and 3D Systems were still two of the biggest names in the industry, churning out a variety of industrial machines, these hard-working understudies were growing in size and stature.

In a huge move at the time, 3D Systems took control of the Selective Laser Sintering market by acquiring DTM in April 2001. The move was worth $45M and saw 3D Systems become market leaders in two different 3D printing technologies: SLA and SLS.

2002: 3D printed bladders, and EnvisionTEC

The 3D printed bladder was merely the start for bioprinting and 3D printing’s ongoing usefulness in medical treatments. In 2002, a 3D printed miniature human kidney was created, again at the Wake Forest Institute for Regenerative Medicine. Though not full size, this represented a key advancement in bioprinting, exciting many that 3D printed organs could solve the shortage of organs available for transplant, and even 3D print hearts.

EnvisionTEC were also established in 2002, who have grown to become a major 3D printing company, selling over 40 printers which are widely used across the jewelry, bioprinting and dental industries.

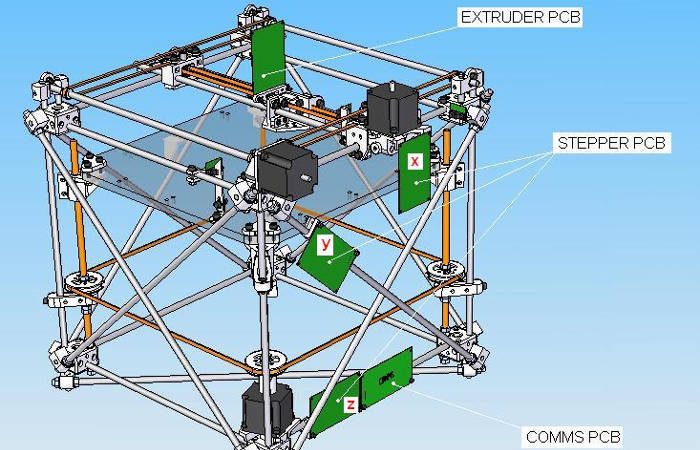

2004 – 05: Beginnings of RepRap, and 3D Printing goes HD

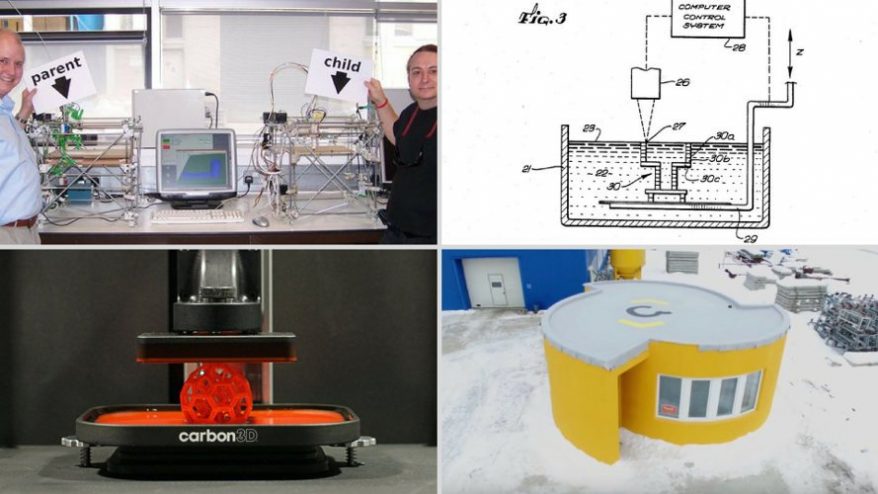

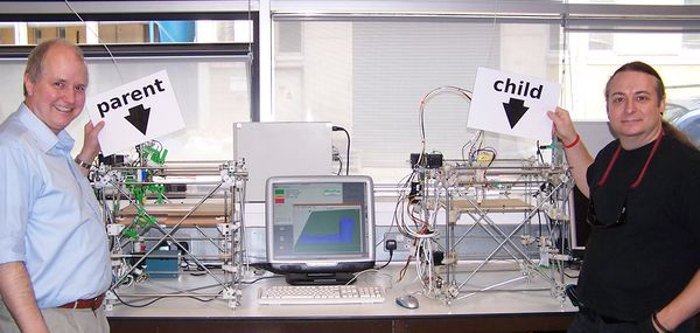

During the years 2004 and 2005, the beginnings of what is arguably the single most important event in 3D printing history occurred. A senior lecturer at the University of Bath, Dr. Adrian Bowyer, had been inspired by 3D printing and had ideas for 3D printers that could self-replicate — building more versions of themselves.

“I’d been interested in self-reproducing machines since I was a child, I don’t really know where that originated — nearly 70 years ago. That was a constant background interest. Though it wasn’t a research activity, I had not done any research into self-replicating machines.

“They [3D printers] were fabulously expensive: the cheapest one when I started the RepRap project cost around £40,000, and in fact that was one of the ones we bought at the university. When I looked at how it worked, it seemed it would be possible to make such a machine at a considerably reduced price, but my primary aim was to produce a machine that could produce most of its parts. And so, that was the way the project went.” — Dr Bowyer, in an interview with 3DSourced.

The movement, named RepRap (short for ‘replicating rapid prototyper’), started off as an initiative within the University of Bath, but later gained popularity worldwide. The project was open source and focused on the spreading of low-cost 3D printing worldwide, leading to its democratization. Interest in these low cost 3D printers skyrocketed as people edited and tinkered with his designs.

- We’ve also ranked the best RepRap 3D printers.

ZCorp were intent on making 2005 their year too however, announcing their Spectrum Z510 3D printer. This wasn’t your average yearly upgrade with marginally improved specs, but a voyage into the unknown which shattered perceived limitations of 3D printing. The Z510 could not only print in color, but was the first 3D printer that could print in color in HD.

2005 – 08: Binder Jetting, RepRap becomes viable

Also in 2005, ExOne was established as a standalone company from the Extrude Hone Corporation. ExOne would go on to become a leader in Binder Jetting 3D printing, capable of 3D printing objects in metal as well as sandstone. Binder Jetting can create full-color sandstone objects, as well as metal parts with very complex geometries.

Whilst corporations were breaking records, Dr. Adrian Bowyer and his RepRap movement were also hard at work with more wholesome goals. The 2008 release of the ‘Darwin’ RepRap 3D printer was huge – the printer could self-replicate, and people could now easily and cheaply 3D print at home if they had moderate technological and technical knowledge.

Dr Bowyer talking about Vik Olliver using the first RepRap to ever print a part of itself:

“It wasn’t very reliable then! And I didn’t know beforehand because that was actually done by Vik Olliver on the other side of the world! In fact, I didn’t know he was going to try and do that before he did, he did and then put up a blog post and that’s how I learned about it. I thought wa-heyyyy! It worked!”

Darwin wasn’t pretty, but it was functional. What used to be an industry dominated by room-sized industrial machines could now be rivaled by machines that fit on top of a washing machine.

Anyone could easily obtain the parts to create their own Darwin, the only rule being that if you received the parts, you were under obligation to 3D print the parts for more Darwins for other enthusiasts. DIY 3D printer kits would go on to have an incredible impact.

2008: Thingiverse, and the begininng of 3D printed prosthetics

Although now widely known, a small website called Thingiverse, owned by a fledgling company called Makerbot launched in 2008. Thingiverse allowed designers to upload their 3D printer models built on various 3D software for others to download for free and print at home. Since everybody loves free stuff, Thingiverse soon took off. It is now in the top 700 most popular websites in the USA, and just outside the top 1,000 websites in the world. Thingiverse now hosts over a million STL files that anyone can download and tinker with.

- We also have a list of 15 of the best sites to download 3D printer files.

Another major event in 2008 was the first 3D printed prosthetic. This extraordinary achievement was compounded by the fact that this prosthetic leg did not need to be assembled, it was 3D printed to function immediately. This opened many people’s eyes to how 3D printing could save time and labor, as fully-assembled objects could be printed from scratch.

The one-off nature of 3D printing also suggested that it would be the perfect method to create customized prosthetics and medical implants based on individual patients’ needs. Instead of the usual several-month lead times for prosthetics, 3D scanners could scan a patients’ arm or leg, and almost immediately begin to create a prosthetic that fit them perfectly.

Now in the present day, thousands of volunteers work to create 3D printed prosthetic hands and arms for children born without them. The project, called E-Nable, encourages people to print their own prosthetic hands to give away, and to develop and improve existing prosthetic models.

- We also have a full feature story on how millions of lives can be improved by 3D printed prosthetics.

Finally in 2008, Stratasys released a new material compatible with their FDM 3D printers. This wasn’t any material however, but a material that was bio-compatible. This opened the door for 3D bioprinting to become far more widely available in the near future.

The years up to the start of 2009 were an adolescence for 3D printing. New technologies became available such as Electron Beam Melting and Binder Jetting, medical advances were made, and the RepRap movement became viable.

In 2009 however, US patent law meant that within a few years 3D printers would become cheap enough for everybody to have one in their home if they wished.

House printing moves forward, and into space

Dr Khoshnevis refined and improved his house 3D printing technology — called Contour Crafting.

“We [managed to first accurately extrude concrete] around 2003. And in 2004 my work became very famous, in the New York Times… and that’s when the world learned about [Contour Crafting], and it inspired a lot of others to go after it.”

However, facing economic disaster after the crash of 2008, the housing market bombed, along with Dr Khoshnevis’ investment from the industry.

“So I had to also chase the money. In 2008, 2009, real estate went down… and with it went construction, and the support I was getting from industry disappeared. So that’s when I started thinking about space.”

Without funding or support, yet fully confident Contour Crafting could change the world, Dr Khoshnevis embarked on his multi-planetary construction 3D printing vision.

The idea was deceptively simple: if we could print concrete on a 3D printer on Earth, an adapted version could be made that could print with locally-sourced lunar regolith to create Moon (or Mars) bases for permanent settlements in the near future.

History of 3D Printing Part 3: 2009 – 2014: FDM & SLA patents expire, worldwide democratization of 3D printing

A patent expired between end tail end of 2008 and the beginning of 2009. Big deal, patents expire all the time right? This patent was owned by a now-very-large company called Stratasys, for Fused Deposition Modeling technology.

FDM is the simplest 3D printing technology; it involves heating up a plastic filament until it melts, and then extrudes it out layer-by-layer. Since the technology could be replicated the most cheaply, business-minded hobbyists and small businesses watched on eagerly for the patent to fall into public domain so they could create their own versions.

The two biggest events in the history of 3D printing, for every day fans, was firstly the development of the RepRap 3D printer. This showed that low cost 3D printers could be done, and that most of the 3D printer parts could be 3D printed by another printer.

The second event was the expiration of the FDM patent. This meant that anyone could not build these cheap 3D printers with no legal issues, and set the tone for incredible advances in the industry.

2009: The first affordable FDM 3D printers

The first affordable FDM 3D printer kit was released in January 2009. It was called the BfB RapMan printer and although it was first, it wasn’t ugly or terrible. Future iterations were made, and perhaps it would have made a bigger impact if the fledgling company we mentioned earlier hadn’t appeared three months later.

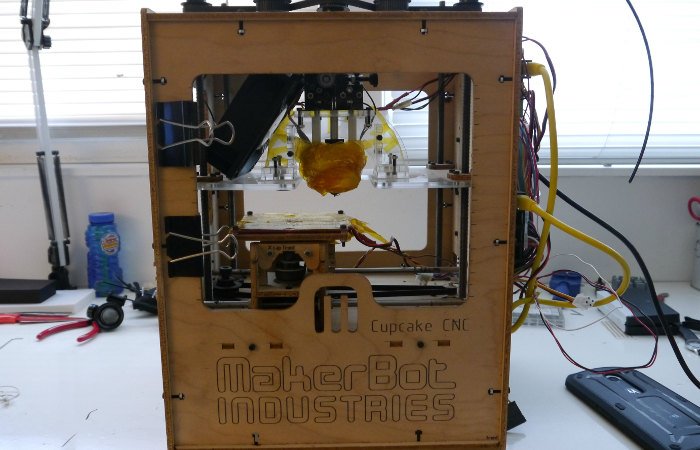

The first Makerbot DIY 3D printer kit released in April 2009. Makerbot were supporters of the open source community, and their first printer, called Cupcake CNC, could be built entirely from parts downloadable from Thingiverse. Demand exploded, and Makerbot had to ask their customers for help to create parts for their backlog of orders. Makerbot were becoming the early kings of affordable desktop 3D printers.

2009 wasn’t just a year for FDM printers however. Organovo, a 3D bioprinting firm, managed to create the first 3D printed blood vessel. This was managed on a new 3D bioprinter which showed significant promise for the future creation of whole organs such as kidneys and hearts.

- We also have a feature story on how close we are to functioning 3D printed hearts.

2009 – 11: Cars, gold jewelry, and the rise of Ultimaker

In recent years, online 3D printing service companies had sprung up to capitalize on the growing demand for 3D printed parts. These services work by allowing users to upload models they have either designed or downloaded, and pay for them to be 3D printed and mailed to their door. Some even allow users to sell their designs on an online marketplace and get paid for their designs.

Companies like Shapeways, Sculpteo, i.materialise, and later 3D Hubs, grew to print hundreds of thousands of parts on demand by the early 2010s. i.materialise then made headlines in 2011 when they were the first to offer 14k gold and sterling silver as 3D printable materials. Anyone who had designed something on their computers at home could (if they had deep enough pockets) have their model 3D printed in gold. The possibilities for custom and high fashion 3D printed jewelry expanded.

Also in 2011, Kor Ecologic produced the first 3D printed car. The car, called Urbee, uses electric motors and gets 200 miles to the gallon.

- Check out our ranking of the most exciting 3D printed car projects.

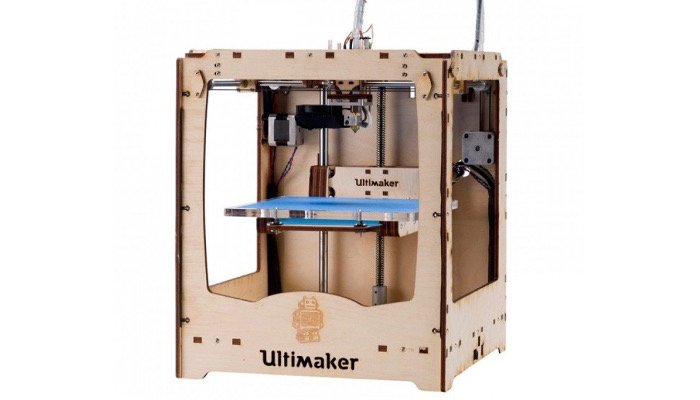

Though Makerbot had dominated the open source, desktop 3D printer market, competition was about to toughen up. Ultimaker was established in 2011 in Geldermalsen, Netherlands, and released the first Ultimaker 3D printer in March 2011. The Ultimaker Original was made from laser-cut plywood and proved an enormous success, launching them into the spotlight.

2012 – 14: The democratization of Stereolithography

Though the original patents for Stereolithography had expired over five years before, nobody had yet been able to create an affordable SLA 3D printer. This changed in June 2012 when the B9Creator released after raising over $500,000 on Kickstarter. The B9Creator utilized a similar technology to Stereolithography called Digital Light Processing (DLP), and could be pre-ordered for $2,375.

6 months later, the affordable resin 3D printer game was changed again, when a new and then unknown startup called Formlabs launched their Kickstarter campaign for a 3D printer called the Form 1. You could pre-order a Form 1 starting at $2,299, and unlike the B9Creator it utilized Stereolithography. The project was an instant hit, raising an almost unprecedented $2.95 million in 30 days. Formlabs have since gone on to release SLS 3D printers, an upgraded SLA 3D printer in the Form 3, and grow to a billoin-dollar valuation.

2012 – 13: Stratasys & Objet merge, Stratasys buys Makerbot

Objet Geometries had gone from strength to strength since the early 2000s, improving their PolyJet technology that could print in full-color. This eventually led to possibly the biggest acquisition in the history of the 3D printing industry. On April 16th 2012, Stratasys announced that it had merged with Objet in an all-stock transaction, with Stratasys being the surviving company. Stratasys would own 55% of this new company, with Objet owning 45%. This gargantuan deal meant the new Stratasys was worth $3 billion at the time.

Stratasys didn’t stop there however. Despite competition from Ultimaker, and open source fans Aleph Objects (who produce Lulzbot 3D printers), Makerbot were still doing very well. On June 23rd 2013, Stratasys announced that Makerbot was the newest item on its shopping list, acquiring the FDM 3D printer giant in a $604M deal, with $403M paid upfront in stock. The founders of Makerbot have all since departed, and their newest machines are no longer open source.

Cody Wilson and the 3D printed gun

Later in 2013, Cody Wilson became a viral sensation after his company Defense Distributed posted an STL file on its site for 3D printing a working 3D printed gun. The US Government ordered Defense Distributed to remove the designs three days later, but the gun had already been downloaded over 100,000 times.

Metal 3D printing has recently become big talk, but before 2015 when tens of startups appeared, the industry was dominated by a few large players like EOS, Arcam and SLM Solutions. 3D Systems’ intent in getting involved in the metal 3D printing sector led to them acquiring French company Phenix Systems in July 2013. 3D Systems paid $15.1M for 81% of the shares and integrated Phenix’s metal 3D printers into their product range.

2014: 3D Printing in space, and SLS and SLA patents expire

A few years after turning his attention to space, Dr Khoshnevis won NASA grand prizes, winning key prize money to further the research.

“We demonstrated at least two technologies that are viable. Technologies for building vertical structures such as hangars, shade walls, radiation protection walls, blast protection walls, and horizontal structures most particularly the landing pads, roads, we demonstrated the feasibility of those entirely to be made with in situ material.

“We actually built… and demonstrated it, that’s why we got Grand Prizes from NASA. My hope and expectation is that those technologies will eventually be used for planetary missions.”

The following year, a more wholesome achievement in 3D printing was realized. NASA announced they had used a 3D printer in space and created the first 3D printed object in space in 2014. This opened the door for future space manufacturing and the ability of future astronauts to create tools on-demand in space. If the team in space needed a particular item, they could be ‘beamed’ the design from Earth at light speed, and 3D print the tool out in space.

2014 was another big year for patents related to 3D printing expiring. First, the major SLS patent expired in 2014, meaning that cheaper alternatives could start being designed by individuals so inclined. Companies like Sintratec and Formlabs worked to create less expensive SLS 3D printers that were still viable. Up until then, most SLS machines were industrial, room-sized behemoths which started at $250,000. This new wave of SLS printers started at $5,000, helping to democratize Selective Laser Sintering.

Moreover, on March 11th 2014 another major 3D printing patent expired. Though Chuck Hull’s original patent had expired a decade earlier, this new patent expiry meant a much more innovative SLA 3D printing process was now in the public domain. Companies such as Formlabs had launched SLA 3D printers a couple of years previously, which patent-holder 3D Systems did not take a shining to. In fact, 3D Systems sued Formlabs in 2012 after they raised their $2.9M from Kickstarter. The case was eventually settled, with Formlabs agreeing to pay an 8% royalty on all sales to 3D Systems.

Though 3D printing had always previously been an industry dominated by a few large firms, this period was especially significant. The two original companies, 3D Systems and Stratasys, solidified their hold on the market by acquiring competitors like Phenix, Makerbot, DTM, Objet, and more.

The industry was far from a monopoly, however. Huge numbers of new competitors offered affordable machines that rivaled industrial 3D printers. Examples include Ultimaker, Lulzbot, and Prusa 3D printers in the desktop and DIY 3D printer kit markets, and Desktop Metal, Markforged, and Carbon 3D in the industrial sector. We will speak more on these newly-mentioned companies in the next part.

History of 3D Printing Part 4: 2015 – Present – Metal 3D printing, cusp of major developments in 3D bioprinting and construction

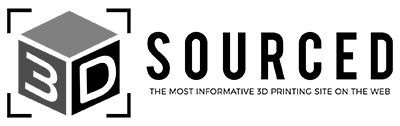

Carbon 3D and Desktop Metal: 0 to $1 billion in 3 years

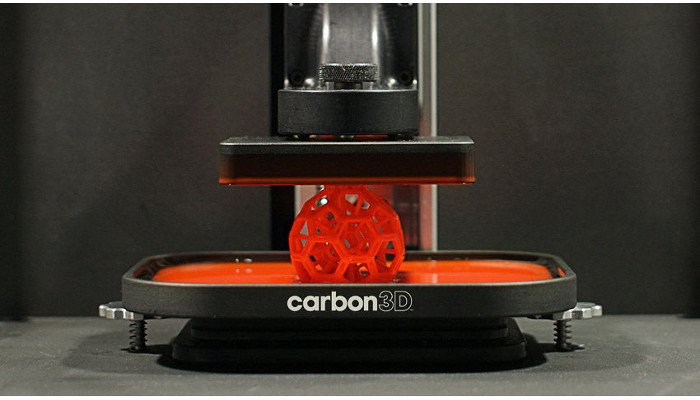

Carbon 3D was formed on July 11th 2014 in California by Joseph and Philip DeSimone. The main tech behind the company was inspired by Terminator 2, and was named CLIP (Continuous Liquid Interface Production). By the end of 2017 the company had raised over $360 million and had a valuation of $1.7 billion – more than Stratasys and 3D Systems (both companies fell sharply in value after the 2013-14 3D printing hysteria died down from valuations in excess of $3 billion previously).

But how did they manage this?

In March 2015, Joseph DeSimone gave the now-viral TED Talk about 3D printing 100x faster. This announced very clearly to the world that Carbon 3D were ones to watch if they could make their CLIP technology feasible. A major grievance of 3D printing was that it was too slow to ever be relied upon as a medium-volume manufacturing option. If Carbon 3D could really print so much faster, it would rival injection molding and other processes for large-volume plastic parts.

They were not the only new 3D printing startup to reach astronomical valuations and receive hundreds of millions of dollars in investment however. Another example is Desktop Metal, who at the same time released their Studio and Production System metal 3D printers.

Since being founded in October 2015, Desktop Metal have received over $200M in investment and the company is now valued at over $1bn. Interestingly, Desktop Metal’s technology, Bound Metal Deposition, is very similar to FDM, just that it works with metal instead. There’s a reason that Silicon Valley investors (as well as Ford, Google, BMW, GE, and more) clamored to invest – their metal 3D printers can print metal 10x cheaper than alternative printers!

Desktop Metal’s Production System metal 3D printer, their more expensive and premium printer, uses a new type of binder jetting technology called Single Pass Jetting. This technology allows for the building of metal parts in minutes, rather than hours as with Direct Metal Laser Sintering. It truly is revolutionary, promising to change metal manufacturing in the near future.

- For more info on recent 3D printing success stories, check out our 15 most valuable 3D printer companies ranking.

Though they may both be innovative, companies like Carbon 3D and Desktop Metal are valued very high compared to their current sales and profits. This is because investors are confident that they will grow to be far bigger and more profitable in the future. This trend occurs in most markets, not just 3D printing.

Take Tesla for example – their revenues are dwarfed by some of the larger carmakers, yet Tesla’s market cap is larger than Ford. This is based on belief that Tesla will become the largest carmaker in the world in the future. We will have to see whether companies such as Carbon and Desktop Metal, as well as others like Markforged, Formlabs and Xact Metal can fulfill their investors’ hopes in the same way.

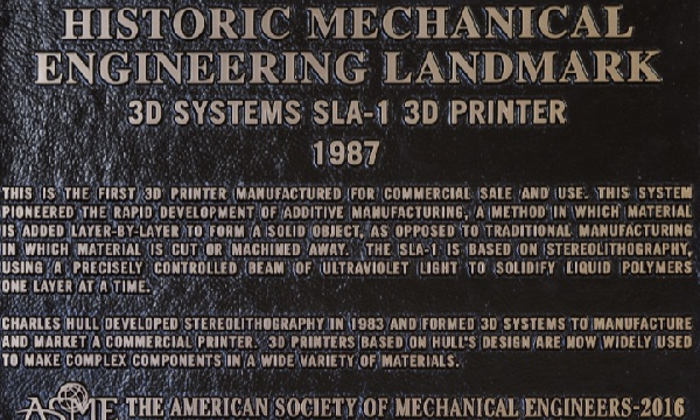

3D Systems enter the Hall of Fame

30 years after 3D Systems had kickstarted the industry, their first ever 3D printer, the SLA-1, was declared a Historic Mechanical Engineering Landmark by the American Society of Mechanical Engineers. This formal recognition of the machine that started it all showed how far 3D printing had come since the 80s.

At around the same time, two very big technology companies entered the market. Household name big.

GE and HP enter

The first was HP, leaders in inkjet 2D printing, who in 2016 announced that they would sell printers featuring their patented Multi Jet Fusion (MJF) technology. HP have since gone on to refine this technology, and in 2018 announced full-color 3D printers, industrial 3D printers at a much lower price range of $50,000, and a move into the metal 3D printing market.

The second household name was GE. Following the incorporation of a new company called GE Additive, the multinational giant acquired metal 3D printing companies Arcam and Concept Laser in late 2016 as part of a $1.4bn move into the additive manufacturing industry. GE Additive also tried to acquire SLM Solutions, but were ultimately unable to.

The incumbents now had HP and GE to worry about too. These deep-pocketed giants could invest billions in gaining a crucial technological advantage, and were now forced to innovate harder than ever. Competition is usually only a good thing for consumers however, as each company worked harder and harder to optimize their technologies to be as effective as possible.

The Ultimaker 3

Regarding the desktop 3D printer market, Ultimaker’s October 2016 release of the Ultimaker 3 was another landmark. It was an instant hit, earning boatloads of Best 3D Printer awards and cementing Ultimaker as a key player in the industry, while remaining committed to the open source philosophy. Ultimaker have since released the S3 and S5, which have received positive reviews.

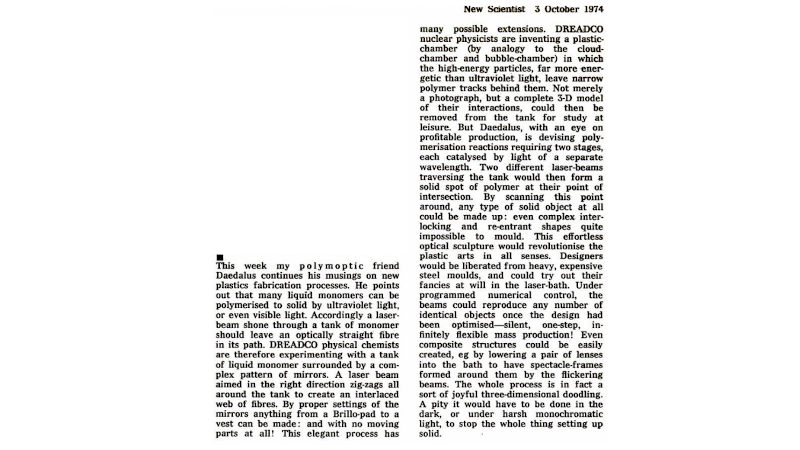

3D printing in construction: a very exciting prospect

But while all these companies were concentrating on 3D printing for manufacturing, others saw it as the solution to the growing housing crisis. 3D printing in construction was a $70M industry in 2017, but reports project it to be worth $40bn by 2027.

Companies such as Apis Cor and WinSun were started, creating huge concrete 3D printers that could build skeletons of houses far quicker and cheaper than any human. This advance was immortalized by Apis Cor 3D printing a whole house in just 24 hours. Other construction and architectural projects involving 3D printing were completed throughout the 2016-2018 period include 3D printed bridges, houses, and even plans for skyscrapers in Dubai.

Ultimaker S5 vs Makerbot Method: The Prosumer 3D Printer Battle 2018/19

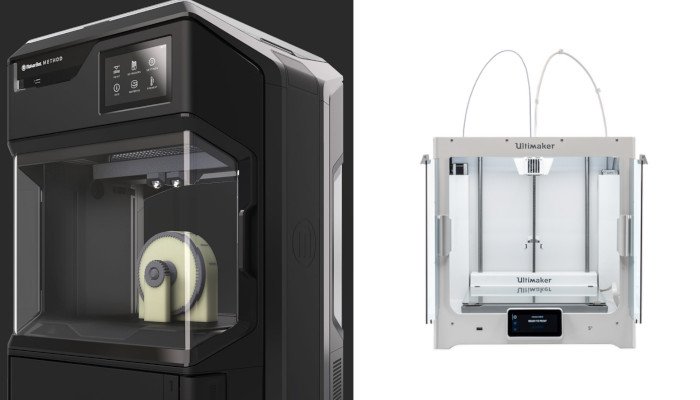

Both Ultimaker and Makerbot grew extraordinarily throughout the mid-2010s, and were flying high off their Ultimaker 3 and Makerbot Replicator ranges respectively. By mid-2018 this battle was to move into the prosumer 3D printer range with the release of the Ultimaker S5 in May 2018, and the Makerbot Method in December. Both represented a step up in price, from around $3,000 up to over $5,000.

This was a change from both companies’ roots. They started building small FDM printers — remember the original kits made of wood? — and were previously more aligned with the RepRap philosophy. This move upmarket is an interesting one, though it is worth noting that Makerbot offer a Replicator+ model catered especially to 3D printing in education, retailing at around $2,000.

The Low Cost LCD 3D Printing Revolution

Resin 3D printers used to cost thousands, and that would only afford you a basic SLA printer. Then Digital Light Processing came along a number of years ago, offering a more scalable and modern alternative.

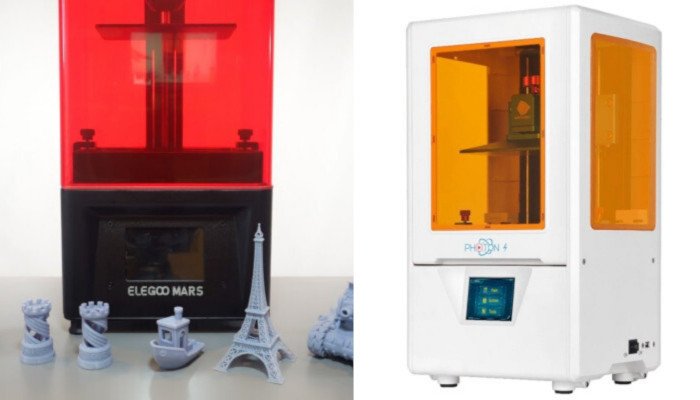

Then it was the turn of LCD 3D printing — more similar in process to DLP than SLA — to usher in the new era of low cost resin printing. Suddenly low cost resin printers like the ELEGOO Mars and AnyCubic Photon offered reasonably accurate resin prints at a printer cost of less than $500. When the first Formlabs printers came out, people found it astonishing that you could print accurate resin objects for $3,500 — oh how things have changed.

- We have a ranking of 5 of the best cheap LCD 3D printers.

World’s Biggest 3D Printed Building: Apis Cor One-Ups Itself

Apis Cor already made headlines when they built a house in 24 hours. Then in October 2019 they went further, building a huge 3D printed building in Dubai. Dubai has been known for its openness to innovative new technologies, especially 3D printing, with this huge structure earmarked for administrative staffing.

Carl Deckard, inventor of SLS, dies at 58

One of the four original 3D printing company founders, Carl Deckard passed away on December 23rd 2019, at the age of just 59. The genius inventor of Selective Laser Sintering had since founded a number of other companies and held 27 patents, and was the most major figure in the history of 3D printing to pass away.

The founders of SLA and FDM, Chuck Hull and S. Scott Crump respectively, are still part of their companies, that are now both public and boast valuations of just under $1 billion dollars. It is unknown how much equity they hold.

EOS’ founder Dr Hans Langer, is 3D printing’s first and currently only billionaire, with an estimated net worth of $3.1bn as of August 2020 according to Forbes. The German company never went public, and is still successful 30 years on in the SLS and DMLS 3D printer markets.